Monday, August 31, 2009

philosophy and mortality

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Starbucks saved his life

Journals do sometimes become books, films, and college lecture tours...

Michael Gates Gill is convocation speaker at Middle Tennessee State University this afternoon, recounting his fall from Master of the Universe at J. Walter Thompson to Starbucks barista, in his sixties. But the happy moral of this story is that the fall was really a rebirth. "Leap to a new life" is his exuberant Kierkegaardian counsel:

"I could never have gotten out of the box I had created for myself [joblessness, unhappiness] if I hadn't leapt without thinking... You can't think your way out of a box. You have to leap, and leap with faith that if you do take a chance, there will be angels of grace who will catch you and help you on your way."

Reading that, I knew why my colleague said Gill's book was bad. But though I'm no Kierkegaardian irrationalist, I disagree. This is a good piece of practical wisdom, for all of us in uncertain times. You can land on your feet and come up smiling, if you're willing to stretch and bend a bit. That's a strong message.

But I won't be endorsing the general proposition, in the classroom, that thinking is a waste of time. Even an irrationalist has to think about the ground he leaps from, if he wants to give himself a fighting chance of landing right-side-up.

My colleague probably also resisted the saccharine homiletic notes in Gill's book, but I think a little sprinkle of pluralism neutralizes the cloying sweetness. I have to agree with Gill on this one too: "By truly seeing each person I met as a unique individual, I discovered a world of amazing variety and surprising wonder..."

Most importantly: "I discovered so late in life that trusting your own heart is your greatest--and only--path to real happiness. It was only through trusting my heart as my guide that I discovered this. I believe everyone is given a unique path to happiness..."

Gill's Dad, btw, was Brendan Gill of The New Yorker.

Here's Michael Gates Gill featured on CBS Sunday Morning, "so much happier serving than I ever was being served." And here he is, speaking with gratitude, at the Google campus:

Saturday, August 29, 2009

Edward Moore Kennedy

Friday, August 28, 2009

We're #57!

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Dingo's kidneys

Really coulda used a Babel Fish at the retreat yesterday, I'd happily have told a few folks where to stick it. (Maybe this will be developed as a killer app for the iTouch, if it hasn't already. There is in fact a translator site at babelfish.altavista.com.) This "argument," btw, is not so different from the way "scholastics" used to think. Some actually still do. And then, of course, there's the design argument for the spaghetti monster.

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

Retreat edu-tainment

Tuesday, August 25, 2009

Desire to (really) learn

Monday, August 24, 2009

"Go"

Sunday, August 23, 2009

"grand bargain"

Saturday, August 22, 2009

Easy living

Friday, August 21, 2009

you ist what you isst

"Exercise Won't Make You Thin." A headline sure to sell magazines, but unlikely to improve the health of our fellow Americans. Time's bad. But catchier than "exercise alone won't make and keep you thin, you have to eat sensibly too." "Der Mensch ist was er isst," as Feuerbach rightly pointed out.

You are what you eat... and do.

Thursday, August 20, 2009

Google Moon

Ever since the July anniverary of the first Apollo moon visit I can't shake the topic. Guess I always thought we'd all be going there by now. The best way to nurture an obsession, no doubt, is by placing its object out of reach. Some, more Stoic-minded than I, can come to terms with that kind of disappointment. They say "I don't want what I can't have." Good for them. But obsessing about the moon does not make me unhappy, quite the reverse in fact.

In Magnificent Desolation, Buzz Aldrin says he could never satisfactorily answer the persistent, obvious, impossible question that's been pushed at him ever since his return to Earth: "What's it like?" But this is a pretty good simulation:

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

Evolution of God

A note from Bill McKibben

Dear Friends,

It's rare that public humiliation and movement building come in one package, but my appearance on The Colbert Report last night was a bit of both.

The interview lasted all of four minutes, but I managed to make my pitch and survive the interview with at least 40% of my dignity intact. If you have friends who aren't necessarily inclined to earnest environmental preaching, this might be a good clip to send them as you try to recruit new activists for the big day of Climate Action on Oct. 24.

You can see my interview with Colbert--and pass it on to your networks--by using the link below:

http://www.350.org/

In the span of just a few years, Stephen Colbert and his Colbert Report have become institutions in the American media landscape. But interesting institutions--the show is comedy, and it's also slightly anarchic. Colbert is brilliant, and more than a little wild: it's not like going on normal, predictable television. That's the drama, and it's why people tune in.

It's also why I was a little more nervous than usual as my evening in the guest's chair approached. i can usually predict the questions I'll be asked--I've heard most of them before. But last night they were coming fast and furious, and out of left field. "What if I start 349.org?"

With a lot of help from friends who'd coached me and psyched me up, I got through just fine--and even made Colbert laugh when I inquired if his self-styled Nation wanted to join the 80 other governments that are backing our target. Best of all, it worked--our servers hummed with thousands of new colleagues.

We're enormously grateful to Stephen and his crew for helping us spread the word-now let's keep this movement moving!

Onwards,

Bill McKibben

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

please pass the BlackBerry

Monday, August 17, 2009

pre-B'Bang?

Time interviews Brian Clegg about his book Before the Big Bang. Interesting. But he's apparently not read his Bertrand Russell: positing a God behind it all just pushes the mystery back a notch, it doesn't solve anything.

Still, it's a natural and reasonable (if not quite intelligible) question: "What came before the Big Bang?"

In your book, you describe the Big Bang theory as having "the feeling of something held together with a Band-Aid."

Scientists will often portray the Big Bang as if it were known fact, but it isn't. It's a theory within a very speculative field of science, cosmology, which is about as speculative as it gets. I'm not saying the Big Bang theory isn't true, but it's a work in progress.So what are some of the theory's major flaws?

There's an expectation that the Big Bang should have produced a rippling effect, almost like an aftershock, where we could see subtle variations in gravity that have carried on ever since then. A lot of money has been spent on experiments to try and detect these gravity waves and they literally have never, ever found anything. Even if they do exist, they're probably not at levels we could detect. And why did it happen at all? There is no sensible answer for the Big Bang unless you move over into the religious side and say, "Well, it began because God began it." That's why quite a lot of scientists are nervous about the Big Bang. They quite prefer having something that doesn't require somebody sort of poking a finger in and saying, "Now it's starting."

Sunday, August 16, 2009

Sleep-deprived

New sleep research is disillusioning for some of us early risers, overconfident that we need no more than six hours in dreamland per night. There are such people, but they're far rarer than we think. "So almost all people who claim they only need six hours' sleep are kidding themselves." But school's starting again. I'm going to keep on kidding myself. A necessary illusion, especially now that I have a new toy.

Saturday, August 15, 2009

Conscious planning

Friday, August 14, 2009

Sweet, Sexy, Cute, Funny...

& inverted. In a brisk TED Talk from earlier this year, Dan Dennett says Darwin's great insight was to turn conventional wisdom about what it means to be sweet, sexy etc. on its head.

In March, Dennett expounded his Darwinian perspective on religion at greater length in London. (You can't break a spell without studying and discussing it in the open.) And in an earlier talk about consciousness, he drew out the implications of questioning authority even with respect to the supposedly intimate awareness of our own minds.

Thursday, August 13, 2009

Scientologists

There was already a "celebrity centre" here on Music Row, now there's another large scientology encampment in the old Fall School building at 8th and Chestnut, near Greer Stadium. A bus-bench ad spotted yesterday in Hillsboro Village encourages all to attend an "Open House" at their convenience. I may just have to drop in before my next Sounds' game, just to get the insiders' account of *Xenu and L. Ron Hubbard.

Hubbard was once quoted as saying that if you want to get rich in America, start a new religion. So he did.

Rolling Stone peeked under the Hubbardites' roof a while back.

This is the "centre" in Hollywood... not too far, coincidentally, from the Magic Kingdom.

What I find especially pernicious about the Scientologists, but possibly not qualitatively distinctive about them in comparison with the more conventional and mainstream ideologies, is the way they compromise their members' ability to think for themselves. "Cult" is the mainstream term of denigration, but we're all cultish to some degree or other... or have cultish tendencies we need to guard against. Insular, single-track, defensive, reactionary "thinking" makes fools of us all. These guys, though, really are over the top.

*In Scientology doctrine, Xenu (alsoXemu or the modern day "Emu" or "Elmo") is an alien ruler of the "Galactic Confederacy" who, 75 million years ago, brought billions of aliens to Earth in DC-8-like spacecraft, stacked them aroundvolcanoes and blew them up withhydrogen bombs. Their souls then clustered together and stuck to the bodies of the living, and continue to wreak chaos and havoc today.» — Wikipedia

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

Good work

Charles Schulz brought, and continues to bring, happiness to millions. He brought it to himself mostly with his work. "Whenever called upon to discuss his life, he made a point of proclaiming himself a failure in all but his work," observed his biographer. Must've been the modest Minnesotan in him. How remarkable that he died on the eve of publication of his last Peanuts strip, after fifty years. He was a good man.

Tuesday, August 11, 2009

Strange Days

"This Modern World," salon.com

done with the dentist

Monday, August 10, 2009

Graham Chapman

The philosophers' song was ridiculous, and entirely false. Graham Chapman's memorial was sublime, honest, and full of sincere affection.

Becoming who you are

Sunday, August 9, 2009

Philosophy, children, nature

Saturday, August 8, 2009

Tolstoy

*What is the best time to do each thing?

*Who are the most important people to work with?

*What is the most important thing to do at all times?

His answers here...

Friday, August 7, 2009

Free-thinking 1st ladies

Isn't it great to have a pair of free-thinkers in the White House again? Thinkers period?

As I grew older I questioned a great many of the things that I knew very well my grandmother who had brought me up had taken for granted. And I think I might have been a quite difficult person to live with if it hadn’t been for the fact that my husband once said it didn’t do you any harm to learn those things, so why not let your children learn them? When they grow up they’ll think things out for themselves.And that gave me a feeling that perhaps that’s what we all must do—think out for ourselves what we could believe and how we could live by it. And so I came to the conclusion that you had to use this life to develop the very best that you could develop.I don’t know whether I believe in a future life....

A future life elsewhere, post mortem, and as herself, I think Mrs. Roosevelt meant. (I like what Andrew Carnegie said about this too, btw: it's not our place to worry about a future life, but to "pitch this one as high as we can.")

But she did believe in our collective future. That's a form of faith, too. I prefer to call it hope.

Thursday, August 6, 2009

so it goes

The anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing is a good day to remember Kurt Vonnegut, whose first-hand experience of the fire-bombing of Dresden shaped his worldview and his fiction. Kindness is still in short supply.

“Hello, babies. Welcome to Earth. It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It’s round and wet and crowded. At the outside, babies, you’ve got about a hundred years here. There’s only one rule that I know of, babies — ‘God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.’ ”

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

Carnegie

I've been enjoying David Nasaw's biography of Andrew Carnegie, who turns out to be a much more sympathetic figure than I'd imagined. He was no Calvinist ascetic, crediting neither divine providence nor personal brilliance for his astounding success. Wealth comes from the community, he thought; the wealthy are its trustees, obliged to give back and do good. And and so he established the precedent lately followed by Gates and Buffett of returning a substantial portion of his personal wealth to the nation whence it sprang. Carnegie libraries all across the country remain the most visible symbol of his largesse.

But he was also a social Darwinist and devotee of Herbert Spencer, and was consequently (and inconsistently) much too smugly confident of the "superior wisdom, experience, and ability" of those "self-made men" who scratch and claw their way to wealth. Credit some of them with superior tenacity but don't understate their superior good fortune.

So he was not humbled by his success, but felt validated by it as a selectee of impersonal social-evolutionary forces. He thought it better that some live in opulent splendor, surrounded by the trappings of civilized culture, than that none should, for this (he claimed) would somehow advance the evolution of humanity. And (though he espoused the virtue of material modesty) he thought himself entitled to partake lavishly of the "good life" that money can buy.

"All is well because all grows better," his slogan, is beyond optimism. Taken literally it becomes a Leibnizian rationalization for everything, including one's own fabulous good fortune. Yet he was no idle defender of the imperialist status quo in foreign policy, turning himself in retirement aggressively towards peacemaking. He opposed Teddy Roosevelt's adventures in Panama and the Phillipines, for instance.

My overall impression of Carnegie, though, as portrayed by Nasaw, is of a humane and generous (albeit egotistical) man, capable of ruthlessness in business but also of great personal loyalty and a real feeling for human beings, whom it would have been a pleasure to know. I wouldn't want to have worked for him. But, tellingly, Mark Twain was a friend (Carnegie sent Scotch, on request). Booker T. Washington was another. A former aid described him as one of the consistently-happiest men he ever knew.

The study of Carnegie's mansion on 91st Street across from Central Park, where he spent the last years of his life giving away much of his fortune, is modest and warm. A visitor had some interesting observations.

The study of Carnegie's mansion on 91st Street across from Central Park, where he spent the last years of his life giving away much of his fortune, is modest and warm. A visitor had some interesting observations.

Carnegie used to spill out of his study and manse (now the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum) and stroll around the Central Park reservoir a time or two on afternoons, perfectly open and accessible. That's another winning detail, to me. The reservoir loop was my last walk in Manhattan, summer-before-last. He'd have been a fun walking companion.

"This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of Wealth: First, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and after doing so to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial result for the community-the man of wealth thus becoming the sole agent and trustee for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer-doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves." Gospel of Wealth

Patronizing, self-aggrandizing, irritating, hypocritcal: sure. People who own castles in Scotland can hardly proclaim their modest lack of ostentation. But if somebody has to be filthy-rich, it's too bad more of them can't be more like him. As patrons go, you could do worse.

Tuesday, August 4, 2009

Too happy?

Is Positive Psychology a victim of its own wide appeal? A new Chronicle essay by Jennifer Ruark ("An Intellectual Movement for the Masses: 10 years after its founding, positive psychology struggles with its own success") worries that the "movement" atrracts too many Fruit Loopy types.

It's not unreasonable to wonder where happy shades into goofy. But, weirdly, some apparently want to exclude practitioners from my academic turf, ground not commonly fought over except by those who would pull it out from under our feet:

"Critics said Seligman's proposal was too radical: He was overstepping the bounds of social science and trying to be a philosopher, telling people how to live their lives."

I hope people don't generally perceive philosophy's function as "telling people how to live," though of course we're all about having that conversation and soliciting (then critiquing, sure) a wide spectrum of views on the subject.

In any event, we really don't feel professionally threatened by Positive Psychology. Happy to have 'em on board, the more the merrier. But I note the stirrings of a backlash against Positive Psych, as seems implicit in this piece in the Times:

Can we only be happy in retrospect? Tim Kreider thinks so.

"I suspect there is something inherently misguided and self-defeating and hopeless about any deliberate campaign to achieve happiness. Perhaps the reason we so often experience happiness only in hindsight, and that chasing it is such a fool’s errand, is that happiness isn’t a goal in itself but is only an aftereffect. It’s the consequence of having lived in the way that we’re supposed to — by which I don’t mean ethically correctly so much as just consciously, fully engaged in the business of living. In this respect it resembles averted vision, a phenomena (sic.) familiar to backyard astronomers whereby, in order to pick out a very faint star, you have to let your gaze drift casually to the space just next to it; if you look directly at it, it vanishes. And it’s also true, come to think of it, that the only stars we ever see are not the “real” stars, those cataclysms taking place in the present, but always only the light of the untouchable past."

And then there's the Happy Meter: Obama makes us happy, blog analysts in Vermont say. Will this very post tip the meter even higher? But let's not get carried away trying to twitter our way to happiness. "We don't want people to be happy all the time; that would be Brave New World... We clearly need a balance of good and bad days to keep us healthy and balanced."

You can have some of my bad ones, Dr. Dodds, if you really think it'll do you some good. I think they're highly over-rated myself. (Here, have some of this tasty Miralax-laced-Gatorade.)

Monday, August 3, 2009

our comestible beginnings

Cooking (not language or tools or bipedalism etc.) made us human, Michael Pollan speculates. Not cooking makes us stooges of the gastro-industrial complex, and bad citizens of the biotic community.

Fascinating, but in my case pretty darn deflating. I'd rather we climbed the evolutionary ladder with aptitudes I actually posssess.

But I can confirm, anecdotally, the basic observation anchoring his concern in this essay: our kids like to watch, too. I found them tuned in to Emeril recently, drooling but not making a move towards the kitchen.

And asking for popcorn.

Speaking of corn: Michael Pollan did a terrific TED Talk too.

Sunday, August 2, 2009

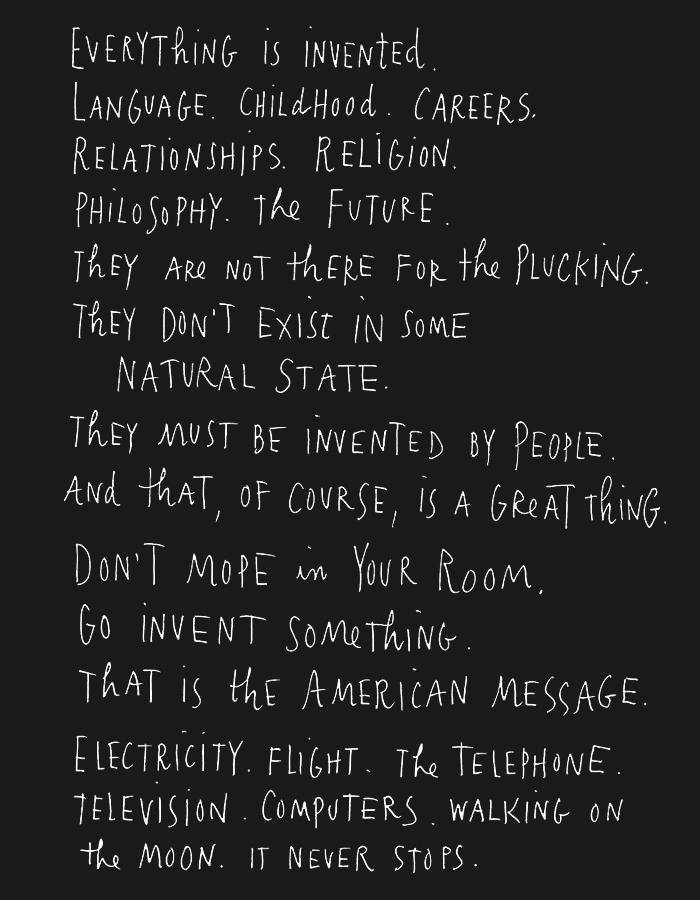

"Can do"

Another terrific slideshow from Maira Kalman, this one on Ben Franklin (following Tom Jefferson).

Hoosier epiphany

Finding comfort with non-belief

Free-thinkers set goal of changing local attitudes

Free thought [is] “a philosophical viewpoint that holds that beliefs should be formed on the basis of science and logical principles and not be compromised by authority, tradition or dogma.” Free thought does encompass atheism and agnosticism, he says, but the group consists of people with many belief systems and anyone is welcome... The group also maintains a Web site at www.freethoughtfortwayne.org and a presence on Facebook and Twitter... The most recent addition: “Dial-an-Atheist,” once-a-month call-in editions of the show in which Chad Butterbaugh of Fort Wayne and others in the group field questions from viewers live.

“An atheist in the broadest sense is simply one who lacks belief in any god or gods – that’s ‘a’ as in ‘not’ or ‘without’ and ‘theism’ as in ‘belief in God or gods,’ ” says Butterbaugh, 29, introducing the June 15 edition, “What is an Atheist?”

“It’s a descriptive term, and that’s all. It’s not an insult, it’s not a club, and it’s not an indicator of some other big, broad philosophy,” Butterbaugh continues, with the bespectacled, earnest demeanor of a 19th-century law clerk.

“And under that definition, I would say that I am an atheist. Jake, comfortable saying that?”

“Oh yeah. I’m an atheist, definitely,” replies co-host Jake Doelling of Fort Wayne with a cheery smile.

“We want people to know we’re normal people. We have our own joys and fears and disappointments and sorrows like everybody else...”

Saturday, August 1, 2009

"Altar call"

We''ve really heard more than enough about the "worries" of angry gun-toting, tea-tossing Christian conservatives, spouting venom about the "Obama-Pelosi-Reed axis of evil," issuing "marching orders to slay the socialist monster" and "altar calls" imploring ill-informed Christian jihadists to smite the Democratic infidels. ("Altar call confronts worries of Christian conservatives," Nashville Tennessean August 1)

We've heard barely a peep, however, from politicians and the press in condemnation of such histrionic hate-mongering.

"Some of the audience wore [para-military] uniforms, and brought their guns."

Terrific. Our legislators said they could, after all.

The Tennessean has done part of its job, reporting the story. When will it do the rest of its job, and take an unequivocal editorial position against hateful and incendiary religious displays? When will its "religion reporting" stop providing an unchallenged platform for hate speech?

If your conscience needs a guide, Tennessean, look to the report Bill Moyers aired last week ("Rage on the airwaves," July 24) and then ask yourself what John Seigenthaler would do.

epicurean success

Has anyone had a better idea about happiness in 2,000 years? What's more important than "pleasure"?

Charles Darwin (

Charles Darwin (