I've been enjoying David Nasaw's biography of Andrew Carnegie, who turns out to be a much more sympathetic figure than I'd imagined. He was no Calvinist ascetic, crediting neither divine providence nor personal brilliance for his astounding success. Wealth comes from the community, he thought; the wealthy are its trustees, obliged to give back and do good. And and so he established the precedent lately followed by Gates and Buffett of returning a substantial portion of his personal wealth to the nation whence it sprang. Carnegie libraries all across the country remain the most visible symbol of his largesse.

But he was also a social Darwinist and devotee of Herbert Spencer, and was consequently (and inconsistently) much too smugly confident of the "superior wisdom, experience, and ability" of those "self-made men" who scratch and claw their way to wealth. Credit some of them with superior tenacity but don't understate their superior good fortune.

So he was not humbled by his success, but felt validated by it as a selectee of impersonal social-evolutionary forces. He thought it better that some live in opulent splendor, surrounded by the trappings of civilized culture, than that none should, for this (he claimed) would somehow advance the evolution of humanity. And (though he espoused the virtue of material modesty) he thought himself entitled to partake lavishly of the "good life" that money can buy.

"All is well because all grows better," his slogan, is beyond optimism. Taken literally it becomes a Leibnizian rationalization for everything, including one's own fabulous good fortune. Yet he was no idle defender of the imperialist status quo in foreign policy, turning himself in retirement aggressively towards peacemaking. He opposed Teddy Roosevelt's adventures in Panama and the Phillipines, for instance.

My overall impression of Carnegie, though, as portrayed by Nasaw, is of a humane and generous (albeit egotistical) man, capable of ruthlessness in business but also of great personal loyalty and a real feeling for human beings, whom it would have been a pleasure to know. I wouldn't want to have worked for him. But, tellingly, Mark Twain was a friend (Carnegie sent Scotch, on request). Booker T. Washington was another. A former aid described him as one of the consistently-happiest men he ever knew.

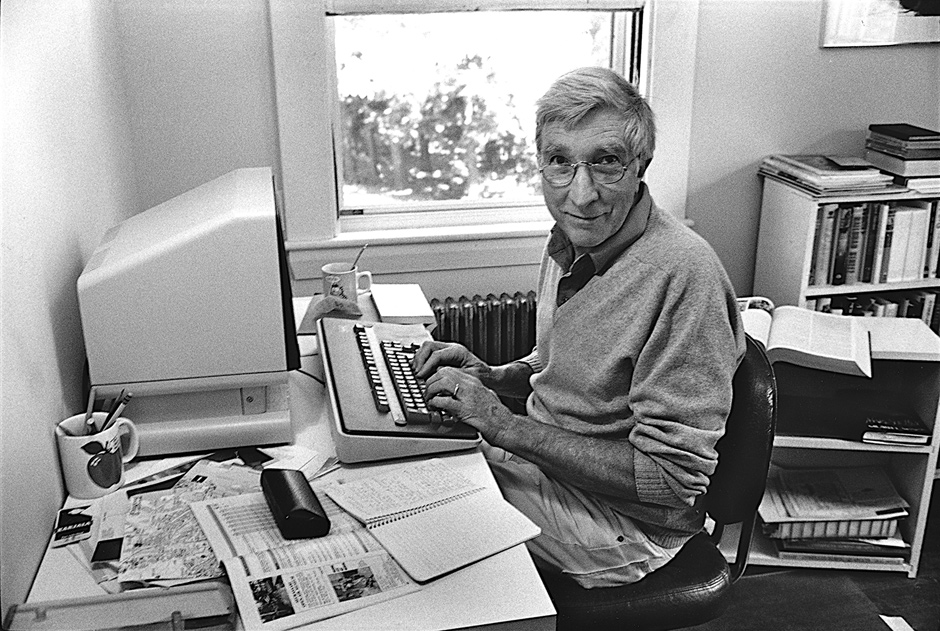

The study of Carnegie's mansion on 91st Street across from Central Park, where he spent the last years of his life giving away much of his fortune, is modest and warm. A visitor had some interesting observations.

The study of Carnegie's mansion on 91st Street across from Central Park, where he spent the last years of his life giving away much of his fortune, is modest and warm. A visitor had some interesting observations.

Carnegie used to spill out of his study and manse (now the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum) and stroll around the Central Park reservoir a time or two on afternoons, perfectly open and accessible. That's another winning detail, to me. The reservoir loop was my last walk in Manhattan, summer-before-last. He'd have been a fun walking companion.

"This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of Wealth: First, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and after doing so to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial result for the community-the man of wealth thus becoming the sole agent and trustee for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer-doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves." Gospel of Wealth

Patronizing, self-aggrandizing, irritating, hypocritcal: sure. People who own castles in Scotland can hardly proclaim their modest lack of ostentation. But if somebody has to be filthy-rich, it's too bad more of them can't be more like him. As patrons go, you could do worse.

Charles Darwin (

Charles Darwin (

No comments:

Post a Comment