Tuesday, December 20, 2022

Earth Stove, R.I.P.

https://www.instagram.com/reel/CmZpzWUptSJ/?igshid=NWQ4MGE5ZTk=

Bookish wisdom

Marilynne Robinson's "Gilead" has been on my reading list ever since Barack Obama went out of his way to meet the author and discuss it with her. I finally started it, and just encountered an uncomfortably humbling insight many of us (I hope) can relate to:

"I’ve developed a great reputation for wisdom by ordering more books than I ever had time to read, and reading more books, by far, than I learned anything useful from, except, of course, that some very tedious gentlemen have written books. This is not a new insight, but the truth of it is something you have to experience to fully grasp."

Gilead: A Novel" by Marilynne Robinson: https://a.co/bicXECY

Thursday, December 15, 2022

How Vast Is the Cosmos, Really?

There are billions of planets in our galaxy, and billions of galaxies in the observable universe. Those numbers are impossible to picture, but NASA's newest space telescope is helping us see the universe's depths in unprecedented detail. Still, there's one big mystery that humans might never be able to solve: How vast is the cosmos, really, and what does it contain?

If humans were to find evidence of life elsewhere in the universe, it would be a scientific marvel, but also an emotional and spiritual one, the physicist Alan Lightman noted in an essay earlier this fall. Our questions would multiply: "Where did we living things come from? Is there some kind of cosmic community?"

Lightman explains why life in the universe is likely really, really rare. "We living things are a very special arrangement of atoms and molecules," he writes. But these questions aren't just about other planets and galaxies; they're also about us, here on Earth, and why we may want to believe that our lives and our stories are one of a kind. What follows is a reading list on why things are the way they are—from life on Earth down to creepy coincidences at the coffee shop—and how we deal with the unknowable.

This is an edition of The Wonder Reader...

Tuesday, December 13, 2022

The joy of (real) reading

What Twitter Does to Our Sense of Time

Wednesday, December 7, 2022

Happy dissolution

Cather only wrote for two or three hours a day. She said, "If I made a chore of it, my enthusiasm would die," she said. "I make it an adventure every day."

Willa Cather's headstone reads, "That is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great." After her death, poet Wallace Stevens said, "We have nothing better than she is."

https://www.garrisonkeillor.com/radio/twa-the-writers-almanac-for-december-7-2022/Tuesday, December 6, 2022

"I stand at the seashore..."

I stand at the seashore, alone, and start to think. There are the rushing waves… mountains of molecules, each stupidly minding its own business… trillions apart… yet forming white surf in unison...Stands at the sea… wonders at wondering… I… a universe of atoms… an atom in the universe.

Sunday, December 4, 2022

Friday, December 2, 2022

Charles Darwin, His Beloved Daughter, and How We Find Meaning in Mortality

In the spring of 1849, ten years before On the Origin of Species shook the foundation of humanity's understanding of life, the polymathic astronomer John Herschel — coiner of the word photography, son of Uranus discoverer William Herschel and nephew of Caroline Herschel, the world's first professional female astronomer — invited the forty-year-old Charles Darwin (February 12, 1809–April 19, 1882) to contribute the section on geology to an ambitious manual on ten major branches of science, commissioned by the Royal Navy. Darwin produced a primer that promised to make good geologists even of readers with no prior knowledge of the discipline, so that they might "enjoy the high satisfaction of contributing to the perfection of the history of this wonderful world."

In submitting his manuscript, Darwin wrote to Herschel:

I much fear, from what you say of size of type that it will be too long; but I do not see how I could shorten it, except by rewriting it, & that is a labour which would make me groan. I do not much like it, but I have in vain thought how to make it better. I should be grateful for any corrections or erasures on your part.

A perfectionist prone to debilitating anxiety, Darwin was vexed by the editorial process. But in the autumn of 1850, just as the manual was about to go to press, trouble of a wholly different order eclipsed the professional irritation: The Darwins' beloved nine-year-old daughter, Annie — the second of their ten children and Charles's favorite, fount of curiosity, sunshine of the household — fell ill with a mysterious ailment...

https://www.themarginalian.org/2021/02/12/annie-darwin/Sunday, November 27, 2022

The Huxleys on evolution, religion, experience, humanism, cosmic philosophy

Julian developed what he called "evolutionary humanism," a mashup of his favorite progressivist themes. It featured in many of his lectures and books, although he discussed it in greatest detail in "Religion Without Revelation" (1927). Central to the ideology was humanity's purpose: we are the children of a cosmic process that produces ever-greater intelligence and complexity. There could be no more important common aim than to take control of that process—to overcome our individual and tribal identities and achieve the more advanced mode of collective existence he called transhumanism. Evolutionary humanism, given its focus on the betterment of the species, became welded to eugenics. This might explain why, as eugenics lost legitimacy, evolutionary humanism became all but forgotten.

Where Julian focussed on unity and transhumanism, Aldous turned to experience. As an undergraduate at Oxford, he wrote to Julian about his conviction that the higher states of consciousness described by mystics were achievable. The fascination persisted, and, by the nineteen-thirties, Aldous believed that society's aim should be to nurture the pursuit of enlightened consciousness. By the time he published "The Doors of Perception" (1954), which connected his experience on the drug mescaline to the universal urge for self-transcendence, he had been writing and lecturing on mystical experiences for decades. Through this commitment, Aldous helped pioneer a form of secular mysticism that suffuses modern attitudes, showing up in things like New Age yoga and psychedelic-assisted therapy. An inheritor of evolution, the half-blind stork wrested sublime experience from the caverns of institutionalized religion.

The history of the Huxleys reveals a paradox in how we think about evolution. On the one hand, it exemplifies our impulse to find answers in cosmology. As organized religion declined, people sought guidance and justification in the scientific narratives taking its place. From race science to eugenics, progress to spirituality, the Huxleys combed our deep past for modern implications, feeding an ever-present yearning.

On the other hand, the Huxleys expose how diverse and historically contingent those implications can be. Evolution is a messy, nuanced, protean picture of our origins. It offers many stories, yet those which we choose to tell have their own momentum. It can serve as a banner of our common humanity or as a narrative of our staggering differences. It can be wielded to fight racism or weaponized to support oppression. It can inspire new forms of piety or be called on to destroy dogma. The social meanings of evolution, like so much else, are part of a grander inheritance.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/11/28/how-the-huxleys-electrified-evolution

Thursday, November 24, 2022

“grateful for every good thing”

Today is Thanksgiving Day. Although the Thanksgiving festivities celebrated by the Pilgrims and a tribe of Wampanoag Indians happened in 1621, it wasn't until 1789 that the newly sworn-in President George Washington declared, in his first presidential proclamation, a day of national "thanksgiving and prayer" for that November.

The holiday fell out of custom, though, and by the mid 1800s only a handful of states officially celebrated Thanksgiving, on a date of their choice. It was the editor of a women's magazine, Sarah Josepha Hale, a widow and the author of the poem "Mary Had a Little Lamb," who campaigned for a return of the holiday. For 36 years, she wrote articles about the Plymouth colonists in her magazine, trying to revive interest in the subject, and editorials suggesting a national holiday. Hale wrote to four presidents about her idea — Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan — before her fifth letter got notice. In 1863, exactly 74 years after Washington had made his proclamation, President Lincoln issued his own, asking that citizens "in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise." He requested prayers especially for those widowed and orphaned by the ongoing Civil War, as well as gratitude for "fruitful fields," enlarging borders of settlements, abundant mines, and a burgeoning population.

It was Ralph Waldo Emerson who suggested, "Cultivate the habit of being grateful for every good thing that comes to you, and to give thanks continuously. And because all things have contributed to your advancement, you should include all things in your gratitude."

In the book On Gratitude, published in 2010, a number of writers take up Emerson's charge, listing some of the specific things that helped them in their writing career — things for which they are grateful. In the book, Kurt Vonnegut said: "I've said it before: I write in the voice of a child. That makes me readable in high school. Simple sentences have always served me well. And I don't use semicolons. It's hard to read anyway, especially for high school kids. Also, I avoid irony. I don't like people saying one thing and meaning the other. Simplicity and sincerity, two things I am grateful for."

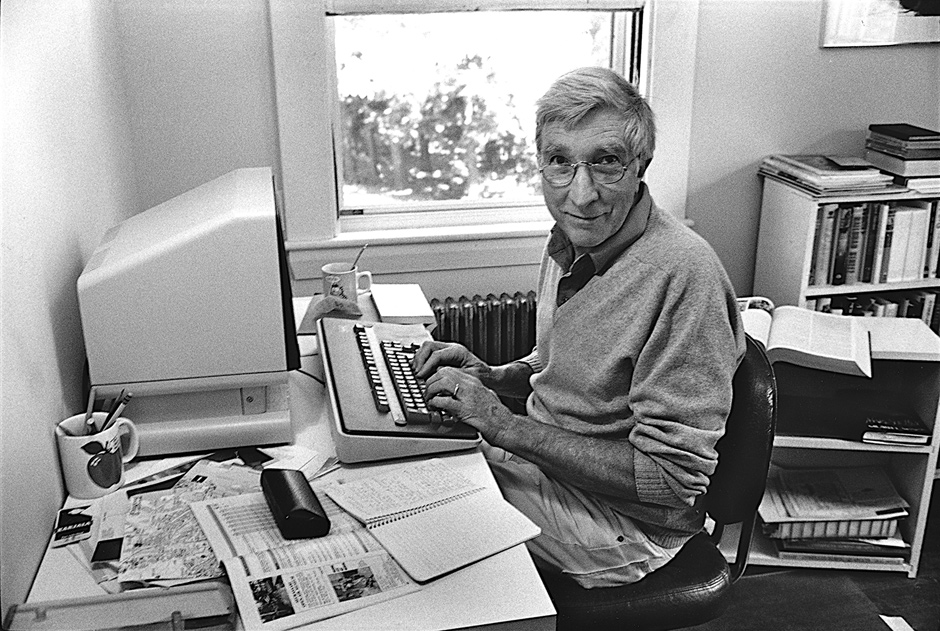

John Updike said: "I'm not a movie star or a rock star. I maybe get two or three letters a week out of the blue, for some reason, and as I'm an old guy now, most of the letters are kindly. They do keep you going. This is an unsponsored job. I don't get paid without readers. So I appreciate that enduring fan base. It does keep me going. And for someone to take the time to say they like me. That's a blessing."

Joyce Carol Oates said: "I was only about eight years old when I first read Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland, and when we're very, very young almost anything that comes into our lives that's special or unique or profound can have the effect of changing us … I virtually memorized most of Alice … That blend of the surreal and the nightmare of the quotidian have always stayed with me. My sense of reality has been conditioned by that book, certainly, and I am grateful for it."

Jonathan Safran Foer said: "I'm grateful for anything that reminds me of what's possible in this life. Books can do that. Films can do that. Music can do that. School can do that. It's so easy to allow one day to simply follow into the next, but every once in a while we encounter something that shows us that anything is possible, that dramatic change is possible, that something new can be made, that laughter can be shared."

https://www.garrisonkeillor.com/radio/twa-the-writers-almanac-for-november-24-2022/

Tuesday, November 22, 2022

Earthset from Orion

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/21/science/nasa-artemis-orion-moon-pictures.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare

How Reading — Not Scanning, Not Scrolling — Opens Your Mind

Every day, we consume a mind-boggling amount of information. We scan online news articles, sift through text messages and emails, scroll through our social-media feeds — and that's usually before we even get out of bed in the morning. In 2009, a team of researchers found that the average American consumed about 34 gigabytes of information a day. Undoubtedly, that number would be even higher today.

But what are we actually getting from this huge influx of information? How is it affecting our memories, our attention spans, our ability to think? What might this mean for today's children, and future generations? And what does it take to read — and think — deeply in a world so flooded with constant input?

…

Ezra Klein Show

Monday, November 21, 2022

Thinking is pedestrian

"There is time enough for a stream of consciousness that flows at the pace of walking. All the parts of your life, all the time scales, smoosh together. This pace is a mode of being: the walking pace, pedestrian and prosy. Thinking is pedestrian. Aristotle’s Peripatetics: they talked things over while walking around the Lyceum, and their walking helped them to think. They felt that. I like the sweaty huff and puff of the uphill slogs, and the meticulous stepping of downhill, and every other part of walking. Of course I also like the rest stops, and setting camp, making dinner, wandering around, watching the sunset, lying down at night; I even like insomnia if it happens to strike me. I like it all. But what you do most of the day up there is walk. And I like that most of all."

"The High Sierra: A Love Story" by Kim Stanley Robinson: https://a.co/03iIPKF

Wednesday, November 9, 2022

“a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam”

It's the birthday of Carl Sagan, born in Brooklyn, New York (1934), who created the TV show "Cosmos", which is still the most popular science program ever produced for television. He was a young astronomer advising NASA on a mission to send remote-controlled spacecrafts to Venus, when he learned that the spacecrafts would carry no cameras, because the other scientists considered cameras to be excess weight. Sagan couldn't believe they would give up the chance to see an alien planet up close. He lost the argument that time, but it's largely thanks to him that cameras were used on the Viking, Voyager, and Galileo missions, giving us the first real photographs of planets like Jupiter and Saturn and their moons.

Sagan also persuaded NASA engineers to turn the Voyager I spacecraft around on Valentine's Day in 1990, so that it could take a picture of Earth from the very edge of our solar system, about 4 billion miles away. In the photograph, Earth appears as a tiny bluish speck. Sagan later wrote of the photograph, "Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives… [on] a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam."

He actually never used the phrase "billions and billions of stars," which is often attributed to him, but Billions and Billions is the title of his last collection of essays, which came out in 1997, the year after he died.

https://www.garrisonkeillor.com/radio/twa-the-writers-almanac-for-november-9-2022/Sunday, October 9, 2022

As the world turns

Credit: Martin Giraud

https://t.co/JG0IcOxWvO

(https://twitter.com/wonderofscience/status/1579086778845233155?s=02)

Saturday, October 8, 2022

How a Scottish Moral Philosopher Got Elon Musk’s Number

...In August, Mr. Musk retweeted Mr. MacAskill’s book announcement to his 108 million followers with the observation: “Worth reading. This is a close match for my philosophy.” Yet instead of wholeheartedly embracing that endorsement as many would, Mr. MacAskill posted a typically earnest and detailed thread in response about some of the places he agreed — and many areas where he disagreed — with Mr. Musk. (They did not see eye to eye on near-term space settlement, for one.)

For his part, Mr. MacAskill accepts responsibility for what he calls misapprehensions about the community. “I take a significant amount of blame,” he said, “for being a philosopher who was unprepared for this amount of media attention.”

In a few short years, effective altruism has become the giving philosophy for many Silicon Valley programmers, hedge funders and even tech billionaires.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/08/business/effective-altruism-elon-musk.html?smid=em-share

Monday, October 3, 2022

Sunday, September 25, 2022

The Next Walk You Take Could Change Your Life

Researchers who study our brain activity while we walk use the term "automaticity" to describe how our body behaves on a stroll. Automaticity is defined as "the ability of the nervous system to successfully coordinate movement with minimal use of attention-demanding executive control resources."

We should leverage the gift of walking to stop thinking and start doing, apparently, what walking is asking us to do — pay attention to the stuff of place, the place itself. To arrive at that point takes time, and discipline, but when it does, delight bubbles up, a "praising of the mysterious and tender touching we are so often in the midst of," according to Ross Gay, poet and author of "The Book of Delights." Place comes to life, any place, from the life we gave it, from attentiveness.

When I walk, I say, "Now I'm walking." I ring a bell in my mind to get prepared. It doesn't matter if I'm going to the store or for a lunchtime stroll to catch a glimpse of a sexy tree — I know I'm walking. I breathe. I swipe left on everything that tries to lodge itself between me and the world. Pebbles crunch underfoot. Leaves smile in my eyes. Sounds emanate from bottomless wells. The world gets younger, exalted. I see, smell, hear and feel things I didn't before. It's not profound, not magic, but it is impossible to tie a ribbon around.

Not everyone can walk. That capacity may be denied to us at birth, or we can lose mobility over time. But walking is, in the end, a metaphor for being, a place and time — a place-time — gifted to us.

We could all use that gift.

Francis Sanzaro is the author of "Zen of the Wild: A Philosophy for Nature," "Society Elsewhere: Why the Gravest Threat to Humanity Will Come From Within," and other books.

Saturday, September 24, 2022

Albert & Yadi

So delighted this happened at Dodger Stadium just before the game in which Albert hit #s 699 & 700...

Friday, September 2, 2022

The oldest VR technology

Gene Roddenberry

https://news.lettersofnote.com/p/i-consider-reading-the-greatest-bargain?r=35ogp&utm_medium=ios

Sunday, August 21, 2022

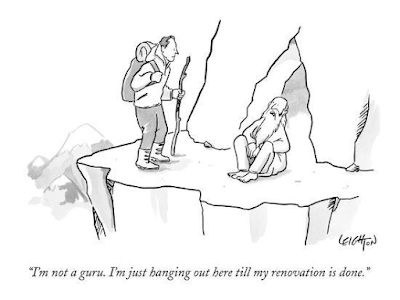

No gurus

I always tell students on Opening Day to resist the Guru model of wisdom. Philosophy is collaborative. Authority figures do not appeal.

"...there is no teacher, no pupil; there is no leader; there is no guru; there is no Master, no Saviour. You yourself are the teacher and the pupil; you are the Master; you are the guru; you are the leader; you are everything." Well, Krishnamurti, I wouldn't go that far.

Future of Humanity Institute

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tuesday, August 16, 2022

Wendell Berry on Delight

"I have always had a quarrel with this country not only about race but about the standards by which it appears to live," James Baldwin told Margaret Mead as they sat down together to reimagine democracy for a post-consumerist world. A generation later, the poet, farmer, and ecological steward Wendell Berry — a poet in the largest Baldwinian sense — picked up the time-escalated quarrel in his slim, large-spirited book The Hidden Wound (public library) to offer, without looking away from its scarring realities, a healing and conciliatory direction of resistance to a culture in which our enjoyment of life is taken from us by the not-enoughness at the hollow heart of consumerism, only to be sold back to us at the price of the latest product, and sold in discriminating proportion along lines of stark income inequality... (continues)

Maria Popova

Sunday, August 14, 2022

characteristic delight

"Unsurprisingly, the back of Either/Or didn’t say which kind of life was better. All it said was: “Does Kierkegaard mean us to prefer one of the alternatives? Or are we thrown back on the existentialist idea of radical choice?” That had probably been written by a professor. I recognized the professors’ characteristic delight at not imparting information."

Either/Or" by Elif Batuman: https://a.co/4q7yZ0f

Saturday, August 6, 2022

If heaven ain't a lot like Wrigley

For some of us, heaven would be listening to Harry & Vin forever. https://t.co/KAekdZ99yc

— Phil Oliver (@OSOPHER) August 6, 2022

Wednesday, August 3, 2022

E B White’s morning dilemma

Friday, July 29, 2022

HDT's bday walk

(https://twitter.com/JohnKaag/status/1552252786775146496?s=02)

Monday, July 18, 2022

Cosmic biocentrism

"With the discoveries of the Kepler satellite in the last five years, it is almost certain that life exists elsewhere in the universe. (Given the unimaginable number of habitable planets, the absence of life beyond Earth would be like the absence of fires in a million dry forests, year after year after year.) The Kepler discoveries, plus the rarity of life in time and in space discussed here, lead to a concept I will call “cosmic biocentrism.” By that, I mean that the rarity and preciousness of life provides a kinship to all living things in the universe. I cannot imagine what kinds of thoughts, what kinds of values and principles, other living beings might have. But we share something in the vast corridors of this cosmos we find ourselves in. What exactly is it we share? Certainly, the mundane attributes of “life”: the ability to separate ourselves from our surroundings, to utilize energy sources, to grow, to reproduce, to evolve. I would argue that we “conscious” beings share something more during our relatively brief moment in the “era of life”: the ability to witness and reflect on the spectacle of existence, a spectacle that is at once mysterious, joyous, tragic, trembling, majestic, confusing, comic, nurturing, unpredictable and predictable, ecstatic, beautiful, cruel, sacred, devastating, exhilarating. The cosmos will grind on for eternity long after we’re gone, cold and unobserved. But for these few powers of ten, we have been. We have seen, we have felt, we have lived."

"Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings" by Alan Lightman: https://a.co/9uRyAum

Saturday, July 16, 2022

A nine-year old confronts the abyss

"My own most vivid encounter with nothingness occurred not while dividing up my kingdom or while contemplating the absence of three-dimensional space in quantum physics, but in a remarkable experience I had as a nine-year-old child. It was a Sunday afternoon. I was standing alone in a bedroom of my home in Memphis, Tennessee, gazing out the window at the empty street, listening to the faint sound of a train passing a great distance away, and suddenly I felt that I was looking at myself from outside my body. For a brief few moments, I had the sensation of seeing my entire life, and indeed the life of the entire planet, as a brief flicker in a vast chasm of time, with an infinite span of time before my existence and an infinite span of time afterward. My fleeting sensation included infinite space. Without body or mind, I was somehow floating in the gargantuan stretch of space, far beyond the solar system and even the galaxy, space that stretched on and on and on. I felt myself to be a tiny speck, insignificant. A speck in a huge universe that cared nothing about me or any living beings and their little dots of existence. A universe that simply was. And I felt that everything I had experienced in my young life, the joy and the sadness, and everything that I would later experience, meant absolutely nothing in the grand scheme of things. It was a realization both liberating and terrifying at once. Then the moment was over, and I was back in my body. The strange hallucination lasted only a minute or so. I have never experienced it since. Although nothingness would seem to exclude awareness along with everything else, awareness was part of that childhood experience, but not the usual awareness I would locate within the three pounds of gray matter in my head. It was a different kind of awareness. I am not religious, and I do not believe in the supernatural. I do not think for a minute that my mind actually left my body. But for a few moments I did experience a profound absence of the familiar surroundings and thoughts we create to anchor our lives. It was a kind of nothingness. Perhaps not Pascal’s nothingness, but a personally experienced nothingness."

"Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings" by Alan Lightman: https://a.co/h5kXmRg

"Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings"

"Iwill tell you a thing that is both impossible and true. You were born from a tiny seed within your mother. And she was born from a tiny seed within her mother. And she from her mother. And so on, back and back through the dim hallways of time until we arrive at a particular cave in Africa, a hundred thousand years in the past, with a particular woman sitting by a fire. That woman knew nothing of cities or automobiles or electricity. But if we could follow her daughters through time, we would eventually arrive at you. If each of those daughters of daughters had pressed an inky thumb on a large piece of parchment, one following the other, there would today be several thousand thumbprints on that parchment, leading from that ancestral woman a hundred thousand years ago to your thumbprint today. If this story does not seem impossible, or at least incomprehensible, let’s go further back in time. According to modern analysis of the DNA of fossil animals, your ancestral mother descended from more primitive creatures, and those from more primitive, until we reach single-celled organisms squirming and gyrating in a primeval sea. And those first living organisms emerged from the billions of random collisions of lifeless molecules, by chance forming things that could spawn more of themselves and tap energy from the roiling sea. And before that, the ancient air of Earth—methane and ammonia and water vapor and nitrogen—blew over the seething volcanoes. And before, the gases swirled and condensed from a cloud in the primeval solar system. I will tell one final story. Every atom in your body except for hydrogen and helium was made in stars long ago and blown into space when those stars exploded—much later to be tossed into the air and soil and oceans of Earth and eventually incorporated into your body. How do we know? Evidence supports the Big Bang theory, which holds that our universe began in a state of extremely high density and temperature and has been expanding and cooling since. In the first moments after t = 0, the universe was far too hot for atoms to hold together. During the first three minutes, the universe cooled enough for the simplest atomic nuclei, hydrogen and helium, to form, but was thinning out too rapidly to make carbon and oxygen and nitrogen and all the other atoms our bodies are made of. According to nuclear physicists, the formation of those atoms occurred hundreds of millions of years later, when gravity was able to pull together large masses of gas to form stars. The temperatures and densities at the centers of those masses again began to mount, starting nuclear reactions, which fused the existing hydrogen and helium atoms into the other atoms in our bodies. Some of those stars exploded, seeding space with the newly forged atoms. With our telescopes, we have seen exploding stars and analyzed the chemical composition of their debris. We have confirmed the theory. If you could tag all the atoms in your body and follow them backward in time, every atom, except for hydrogen and helium, would return to a star. We are as certain of this story as we are that the continents were once joined. Less certain but supported by compelling calculations are the infinities, the infinity of the small and the infinity of the large. The unending world of ever smaller things within the atom, and the unending world of ever larger things, beyond our telescopes. Between these two endpoints of the imagination are we human beings, fragile and brief, clutching our thin slice of reality."

Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings" by Alan Lightman: https://a.co/f0gAREE

The Watched Walker

I'll bet Walt Whitman woulda watched the Watched Walker...

Wednesday, July 13, 2022

Douglas Adams reads...

In the beginning the Universe was created.

This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move."

There is another theory which states that this has already happened."

Friday, July 8, 2022

Frank Bascombe’s Jersey

https://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/25/books/25ford.html?referringSource=articleShare

Tuesday, July 5, 2022

How to Sacrifice

Thanks, Gary.

How to Sacrifice

by Mick CochranePivot in the box. Square up.

Surrender to the pitcher.Slide your top hand up the barrel,

don't squeeze, keep your handssoft, bend your knees.

You need to keep your balance.Let the ball come to you––

be patient. Don't stab at it.Point your bat, absorb the shock,

and hope the ball stays fair.Afterwards expect no high-fives,

no headlines, no contractextension. No one bunts

himself onto an all-star team.You do it because that runner

on first, he needs to come home.He's your teammate,

he's your brother, he's your son,and you, you're the guy who still

knows how to lay one down.

"How to Sacrifice" by Mick Cochrane from Southern Poetry Review, 55.2.

Thursday, June 30, 2022

Beachy Head

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Saturday, June 25, 2022

Aristotle's springs of delight

"When deciding a plan the most important principle is pleasure. Aristotle regards pleasure as a wonderful tool for scientific, social and psychological analysis of any kind. This is because he believes nature uses pleasure to help all sentient animals find and do what they need to flourish. Different animals are endowed with slightly different ways of feeling pleasure: asses like eating chaff, but dogs like hunting game birds and small mammals. Humans are remarkable because they evince such a diversity of pleasures, distributed across the population. “One man’s meat is another man’s poison.” You may like eating fish; your spouse pork sausage. But this wide diversity applies to far more than our taste in food. Aristotle argues that occupations which afford pleasure are the ones which we should all be aiming at: Life is a form of activity, and each person exercises his activity upon those objects and with those faculties which he likes the most: for example, the musician exercises his sense of hearing upon musical tunes, the student his intellect upon problems of philosophy, and so on. And the pleasure of these activities perfects the activities, and therefore perfects life, which all men seek. Men have good reason therefore to pursue pleasure, since it perfects for each his life, which is a desirable thing. Aristotle noticed that people who get pleasure from their work are almost always best at it. He says that only people who delight in geometry become proficient at it, and the same goes for architecture and all the other arts."

"Aristotle's Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life" by Edith Hall https://a.co/gSAD98Y

Faulty vision

"Among my own circles of often hyper-educated friends and colleagues in the chattering classes there are far too many parents who impose their own vision of the ideal career or lifestyle on their children. One imagined, on zero evidence, that his three-year-old son was destined to become a world-class solo pianist (ten years later the son refused ever to practice the instrument again). What the boy actually liked doing, it seemed to me, was cooking, camping and orienteering. Another acquaintance ignored her daughter’s passion for engineering and forced her to take literary subjects at school and university; she has ended up bitter and frustrated, but at least gets to fix things now that she’s become a plumber."

"Aristotle's Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life" by Edith Hall: https://a.co/6IDiapY

Thursday, June 23, 2022

The peripatetic highway to happiness

"The traditional name for Aristotle’s school of thought is Peripatetic philosophy. The word “Peripatetic” comes from the verb peripateo, which in Greek, both ancient and modern, means “I go for a walk.” Like his teacher Plato, and Plato’s teacher Socrates before him, Aristotle liked to walk as he reflected; so have many important philosophers since, including Nietzsche, who insisted that “only ideas gained through walking have any worth at all.” But the ancient Greeks would have been puzzled by the romantic figure of the lone wandering sage first celebrated in Rousseau’s Reveries of the Solitary Walker (1778). They preferred to perambulate in company, harnessing the forward drive their energetic strides generated to the cause of intellectual progress, synchronizing their dialog to the rhythm of their paces. To judge from the magnitude of his contribution to human thinking, and the number of seminal books he produced, Aristotle must have tramped thousands of miles with his students across craggy Greek landscapes during his sixty-two years on the planet. There was an intimate connection in ancient Greek thought between intellectual inquiry and the idea of the journey. This association stretches far back in time beyond Aristotle to the opening of Homer’s Odyssey, where Odysseus’ wanderings allow him to visit the lands of many different peoples “and learn about their minds.” By the classical period, it was metaphorically possible to take a concept or idea “for a walk”: in a comedy first produced in Athens about twenty years before Aristotle was born, the tragedian Euripides is advised against “walking” a tendentious claim he can never substantiate. And a medical text attributed to the physician Hippocrates equates the act of thinking with taking your mind out for a walk in order to exercise it: “for human beings, thought is a walk for the soul.” Aristotle used this metaphor when he began his own pioneering inquiry into the nature of human consciousness in On the Soul. He says there that we need to look at the opinions of earlier thinkers if we hope “to move forward as we try find the necessary direct pathways through impasses”: the stem word here for a “pathway through” is a poros, which can mean a bridge, ford, route through ravines, or passageway through narrow straits, deserts and woods. He opens his inquiry into nature in his Physics with a similar invitation to us to take not just to the path but to the highway with him: the road (hodos) of investigation needs to set out from things which are familiar and progress toward things which are harder for us to understand. The standard term for a philosophical problem was an aporia, “an impassable place.” But the name “Peripatetic” stuck to Aristotle’s philosophy for two reasons. First, his entire intellectual system is grounded in an enthusiasm for the granular, tactile detail of the physical world around us. Aristotle was an empirical natural scientist as well as a philosopher of mind, and his writing constantly celebrates the materiality of the universe we can perceive through our senses and know is real. His biological works suggest a picture of a man pausing every few minutes as he walked, to pick up a seashell, point out a plant, or call a pause in dialectic to listen to the nightingales. Second, Aristotle, far from despising the human body as Plato had done, regarded humans as wonderfully gifted animals, whose consciousness was inseparable from their organic being, whose hands were miracles of mechanical engineering, and for whom instinctual physical pleasure was a true guide to living a life of virtue and happiness. As we read Aristotle, we are aware that he is using his own adept hand to inscribe on papyrus the thoughts that have emerged from his active brain, part of his well-exercised, well-loved body. But there is just one more association of the term “Peripatetic.” The Greek text of the Gospel of Matthew tells us that when the Pharisees asked Jesus of Nazareth why his disciples didn’t live according to the strict Jewish rules of ritual washing, the verb they used for “live” was peripateo. The Greek word for walking could actually mean, metaphorically, “conducting your life according to a particular set of ethical principles.” Rather than taking a religious route, Aristotle’s walking disciples chose to set out with him on the philosophical highway to happiness."

"Aristotle's Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life" by Edith Hall: https://a.co/8YfVaNZ

Seaside afterglow

Wednesday, June 22, 2022

Roger Angell: in Memoriam

Roger Angell: in Memoriam

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/roger-angell-in-memoriam/

Monday, June 20, 2022

Quote from Two Wheels Good: The History and Mystery of the Bicycle by Jody Rosen

— Two Wheels Good: The History and Mystery of the Bicycle by Jody Rosen

https://a.co/7sS3TgA

Saturday, June 18, 2022

"a responsibility to create the conditions for happiness"

"The subject of Gross National Happiness comes up often in Bhutan. GNH is both an emblem and a conundrum—a point of pride but also a subject of disquisition, debate, and confusion. Many in Bhutan find it hard to articulate exactly what GNH is. Many contend that the concept is misunderstood. Some observers of Bhutanese politics suggest that GNH is not so much profound as it is nebulous—less a philosophy than a brand or a slogan, vague enough to appeal to all comers, notably tourists with excitable Orientalist imaginations and ample spending money. Kinley Dorji is one of the people most often asked to explain GNH. For years he worked as a journalist—he is the former editor-in-chief of Kuensel, Bhutan’s national newspaper—and there is still a hint of ink-stained wretch in his gruff manner. But by the time I met with him, he had moved on to a different job, as the head of Bhutan’s Ministry of Information and Communications, working out of a pleasant office in a Thimphu compound that houses many government ministries. “Here is the key point on GNH,” he said. “Happiness itself is an individual pursuit. Gross National Happiness then becomes a responsibility of the state, to create an environment where citizens can pursue happiness. It’s not a promise of happiness—it’s not a guarantee of happiness by the government. But there is a responsibility to create the conditions for happiness.” Dorji said: “When we say ‘happiness,’ we have to be very clear that it’s not fun, pleasure, thrills, excitement, all the temporary fleeting senses. It is permanent contentment. That lies within the self. Because the bigger house, the faster car, the nicer clothes—they don’t give you that contentment. GNH means good governance. GNH means preservation of traditional culture. And it means sustainable socioeconomic development. Remember that GNH is a pun on GDP, gross domestic product. We are making a distinction.”"

Two Wheels Good: The History and Mystery of the Bicycle" by Jody Rosen: https://a.co/hpYaSDR

Happy pedaling

"In 2006, the king shocked his subjects by unilaterally ending Bhutan’s absolute monarchy. He led an effort to draft a constitution and institute democracy. In 2008, the country held its first general election. Outside Bhutan, the fourth king is best known for his contribution to what might be called political philosophy. It was he, the story goes, who formulated the concept of Gross National Happiness, Bhutan’s “guiding directive for development,” an ethos of holistic civic contentment based on principles of good governance, environmental conservation, and the preservation of traditional culture. Gross National Happiness, or GNH, has made Bhutan a fashionable name to drop in international development circles and a tourist destination for well-heeled, usually Western, New Age seekers. Somewhere along the way, the king took up cycling. It is rumored that he learned to ride when he attended boarding school in Darjeeling, about seventy-five miles from Bhutan’s western border. His education continued in England, at the Heatherdown School, in Berkshire, whose stately campus was crisscrossed by pupils on bikes, commuting between dormitories, classrooms, and cricket greens. Eventually, the Bhutanese royal family imported a bicycle to Bhutan. According to one story, it was a Raleigh racing bike, manufactured in Hong Kong, which arrived in parts and was assembled “upside down” by servants. The defect was spotted by Fritz Mauer, a Swiss friend of the royal family, who personally rebuilt the bike. The now-functional bicycle became a favorite possession of the young crown prince, who often took cycling trips in the dense forests abutting various royal family residences. He became famous—infamous, in the circles of nervous courtiers—for riding “along mud trails at perilous speed.” The royal family’s bicycle was possibly the first bike in Bhutan, and Bhutan may well have been the last place on earth the bicycle reached. Prior to 1962, the country had no paved roads. Today, Bhutan remains, by the usual standards, inhospitable to cycling. It is, almost certainly, the world’s most mountainous nation. The average elevation in Bhutan is 10,760 feet. According to one study, 98.8 percent of the country is covered by mountains. Its roads twist through daunting climbs and hairy descents. Its rugged off-road trails, mottled with rocks and caked in mud, pose a challenge to the sturdiest bicycle tires and suspension systems. Yet today there are thousands of bicycles in Bhutan, and the number is growing. In Thimphu, a city of about one hundred thousand with no traffic lights, bikes scramble up the hilly streets, navigating the one major intersection, where smartly dressed police officers direct traffic from an ornate gazebo that stands in the center of a roundabout. Meanwhile, government officials are increasingly voicing the aim “to make Bhutan a bicycling culture.” The idea is not altogether surprising, given Bhutan’s commitment to environmentalism and sustainability. Still, the idea of a “bicycling culture” taking root in the Himalayas is by definition eccentric. It is no coincidence that the societies that have most successfully integrated cycling into civic life are in northern Europe, where the countries are, as the saying goes, low. The cycling fad in Bhutan is also noteworthy because the story begins with a king and his bike. We know this is not unprecedented: if we riffle the pages of history, we find various places in which bicycles first reached sovereigns and the sovereign-adjacent. But in the twenty-first century, at least, cycling fever does not typically spread from palaces to the people. “There is a reason we in Bhutan like to cycle,” says Tshering Tobgay, who served as Bhutan’s prime minister for five years, from 2013 to 2018. “His Majesty the fourth king has been a cyclist, and after his abdication, he cycles a lot more. People love to see him cycle. And because he cycles, everybody in Bhutan wants to cycle, too.”"

Start reading this book for free: https://a.co/5Bj1AuQ

Tuesday, June 14, 2022

Beached

Tybee Island GA

Early morning beach walk, a blessing the whole day pic.twitter.com/uY4cejeTI0

— Phil Oliver (@OSOPHER) June 14, 2022

— Phil Oliver (@OSOPHER) June 13, 2022By day 3, not this guy anymore:

Friday, June 10, 2022

Two Wheels Good

— Two Wheels Good: The History and Mystery of the Bicycle by Jody Rosen

https://a.co/3bTlJjF

Quote from The Human Cosmos: Civilization and the Stars by Jo Marchant

— The Human Cosmos: Civilization and the Stars by Jo Marchant

https://a.co/17AXDNb

Charles Darwin (

Charles Darwin (