"In 2006, the king shocked his subjects by unilaterally ending Bhutan’s absolute monarchy. He led an effort to draft a constitution and institute democracy. In 2008, the country held its first general election. Outside Bhutan, the fourth king is best known for his contribution to what might be called political philosophy. It was he, the story goes, who formulated the concept of Gross National Happiness, Bhutan’s “guiding directive for development,” an ethos of holistic civic contentment based on principles of good governance, environmental conservation, and the preservation of traditional culture. Gross National Happiness, or GNH, has made Bhutan a fashionable name to drop in international development circles and a tourist destination for well-heeled, usually Western, New Age seekers. Somewhere along the way, the king took up cycling. It is rumored that he learned to ride when he attended boarding school in Darjeeling, about seventy-five miles from Bhutan’s western border. His education continued in England, at the Heatherdown School, in Berkshire, whose stately campus was crisscrossed by pupils on bikes, commuting between dormitories, classrooms, and cricket greens. Eventually, the Bhutanese royal family imported a bicycle to Bhutan. According to one story, it was a Raleigh racing bike, manufactured in Hong Kong, which arrived in parts and was assembled “upside down” by servants. The defect was spotted by Fritz Mauer, a Swiss friend of the royal family, who personally rebuilt the bike. The now-functional bicycle became a favorite possession of the young crown prince, who often took cycling trips in the dense forests abutting various royal family residences. He became famous—infamous, in the circles of nervous courtiers—for riding “along mud trails at perilous speed.” The royal family’s bicycle was possibly the first bike in Bhutan, and Bhutan may well have been the last place on earth the bicycle reached. Prior to 1962, the country had no paved roads. Today, Bhutan remains, by the usual standards, inhospitable to cycling. It is, almost certainly, the world’s most mountainous nation. The average elevation in Bhutan is 10,760 feet. According to one study, 98.8 percent of the country is covered by mountains. Its roads twist through daunting climbs and hairy descents. Its rugged off-road trails, mottled with rocks and caked in mud, pose a challenge to the sturdiest bicycle tires and suspension systems. Yet today there are thousands of bicycles in Bhutan, and the number is growing. In Thimphu, a city of about one hundred thousand with no traffic lights, bikes scramble up the hilly streets, navigating the one major intersection, where smartly dressed police officers direct traffic from an ornate gazebo that stands in the center of a roundabout. Meanwhile, government officials are increasingly voicing the aim “to make Bhutan a bicycling culture.” The idea is not altogether surprising, given Bhutan’s commitment to environmentalism and sustainability. Still, the idea of a “bicycling culture” taking root in the Himalayas is by definition eccentric. It is no coincidence that the societies that have most successfully integrated cycling into civic life are in northern Europe, where the countries are, as the saying goes, low. The cycling fad in Bhutan is also noteworthy because the story begins with a king and his bike. We know this is not unprecedented: if we riffle the pages of history, we find various places in which bicycles first reached sovereigns and the sovereign-adjacent. But in the twenty-first century, at least, cycling fever does not typically spread from palaces to the people. “There is a reason we in Bhutan like to cycle,” says Tshering Tobgay, who served as Bhutan’s prime minister for five years, from 2013 to 2018. “His Majesty the fourth king has been a cyclist, and after his abdication, he cycles a lot more. People love to see him cycle. And because he cycles, everybody in Bhutan wants to cycle, too.”"

Start reading this book for free: https://a.co/5Bj1AuQ

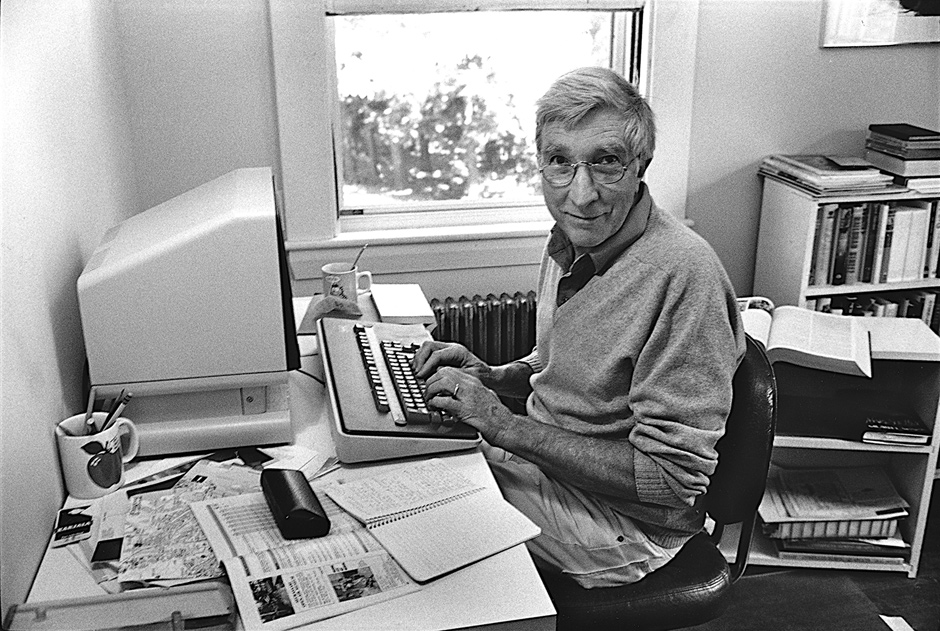

Charles Darwin (

Charles Darwin (

No comments:

Post a Comment